Solution Focused Education – the positive pathway to wellbeing and behaviour for learning

How can we get children to behave properly in school, to take their work seriously and stop messing about?

The answer offered by the DfE is to do more of what’s done already. Focus on the bad behaviour you can see, put aside thinking about what might underly it, and apply graded punishment it until it stops. Knowing what children find unpleasant the pain can be applied in steps, from the sting of social shaming in class, through intentionally distressing social isolation to permanent dislocation and exclusion from the familiar community of school. It’s simple, with no need to make allowances for individuals, or the links between extant behaviour and trauma or learning disabilities. It’s claimed to be “evidence-based” (Bennett 2021 ‘Running the room’) – the highest approval for any intervention in schools.

The weakness in this argument is that it relies heavily on evidence that was generated well over a century ago, from laboratory experiments using dogs, rats and pigeons as models of learning in people. Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) explored what he termed the conditioned reflex, his dogs automatically salivating to the sound of a bell paired with the sight of food. In designing his experiments on live animals he ruled out the subjective component, despite the fact that he could see the stress they experienced. He insisted that it was only possible to deal scientifically with mental phenomena by reducing them to measurable physiological quantities. But there’s a major flaw in this theory of conditioning which is clearly advocated by those promoting the strict discipline behaviour management approach when it is used to modify or control the behaviour of children. Children respond to rewards and punishments subjectively, they do feel happy or sad and we know it.

Bringing the child as a person into the centre of the work by paying attention to their hopes and strengths provides an alternative pathway to the conventional discipline and punishment routine.

Creating relationships which build children’s strengths and resources as the foundation for better behaviour is strongly supported today from an area of research and practice that is still largely unacknowledged in UK schooling and Governmental thinking.

This strengths focused approach was set in train by Carl Rogers, an American psychotherapist and educator (1902-1987) from the 1960s onwards. The 1980s was a time of radical change in thinking about how problems in peoples’ lives could be solved. Solution Focused Brief Therapy, the clinical forerunner of my own application of Solutions Focused Coaching in Schools, was developed by Steve de Shazar and Insoo Kim Berg at about same time as the psychologist Martin Seligman was getting underway with his explanation of Positive Psychology in the USA.

Seligman, taking up his new role as president of the American Psychological Society, gave his 1981 inaugural speech on Positive Psychology. Focusing on strengths and successes rather than on disorder and failures as was the previously dominant psychological approach created a wave of change. It meant moving on from the preoccupation with disease and distress to look at the other side of our lives, those moments when we are well, at our best, flourishing, healthy, happy and engaged.

(Seligman’s 1981 “Authentic Happiness: Using the the New Positive Psychology to Realise your Potential” gives us a picture of the world before Positive Psychology and the possibilities of this new perspective on learning, change and growth. Have a look at www.authentichappiness.org to see how Dr. Seligman has developed this concept over the ensuing 40 years.)

(Retrieved from authentichappiness.com 12/11/2021)

The reward and punishment approach carries with it an unexamined element in behaviour management practice times at correcting ‘bad’ behaviour. Those advocating the behaviourist consequences model of behaviour management argue that teachers are not therapists and have neither the professional training nor the time to attempt to diagnose the causes of the range of displayed ‘misbehaviours’, from withdrawal and disengagement to active disruption. To accurately target an intervention at a child’s behaviour a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist carries out a diagnosis of some type. The behaviourists advise educators to stick with conditioning by reward and punishment. If this doesn’t produce behaviour change it shows that the child has an inherent weakness or disorder that requires their removal from mainstream school to costly specialist provision, where they can be diagnosed and treated.

This argument fails if the only alternative to clinical diagnosis is conditioning through reward and punishment, failing to recognise a different way of working which is in already in place in many schools in some form.

Where the strict discipline approach points up what children should not do, it doesn’t make clear what the child should do instead. It’s attempting to train children to develop automatic reflexes by taking an approach to teaching and learning which is not used in any other part of the school curriculum.

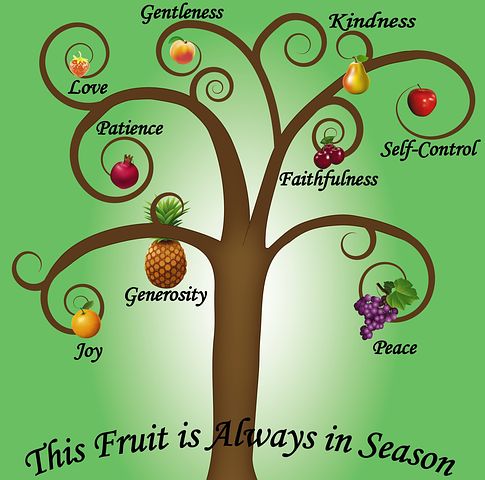

In contrast the solution focused approach aligns with the inquiry teaching approach that centres on what the child can do to make a difference, on the principle that a problem disappears when its solution is in place. This is at the heart of Solutions Focused Coaching in Schools. It matches with Seligman’s strengths-based approach in the Penn Resiliency Programme and Perry’s trauma aware Neurosequential model, with their emphasis on positive emotions, building engagement in learning and the self-motivated strengthening in resilience and self-belief, with behaviour change as an outcome. Daniel Pink (“Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us”) describes a similar idea placing autonomy (the expression of personal agency), meaning and purpose leading to self-motivated change.

Solutions Focused Coaching builds children’s wellbeing and behaviour for learning. It offers a viable alternative to the behaviourist problem-focused approach when children’s needs exceed its capacity to bring about positive change, wellbeing and engagement.