School attendance – a complex issue

Recently a number of threads have been drawing together, connecting children’s behaviour and their mental health and wellbeing, school attendance, exclusion and the various approaches to supporting and managing these vital factors in children’s lives.

One thread is the new DfE drive to “improve the consistency of school attendance support and management”, proposing teams of attendance advisors, and an ‘attendance alliance’ of education leaders, setting up a consultation on its proposals. This looks promising if it opens up the field of evidence now available on the meaning and causes of attendance difficulties and what effective support is possible.

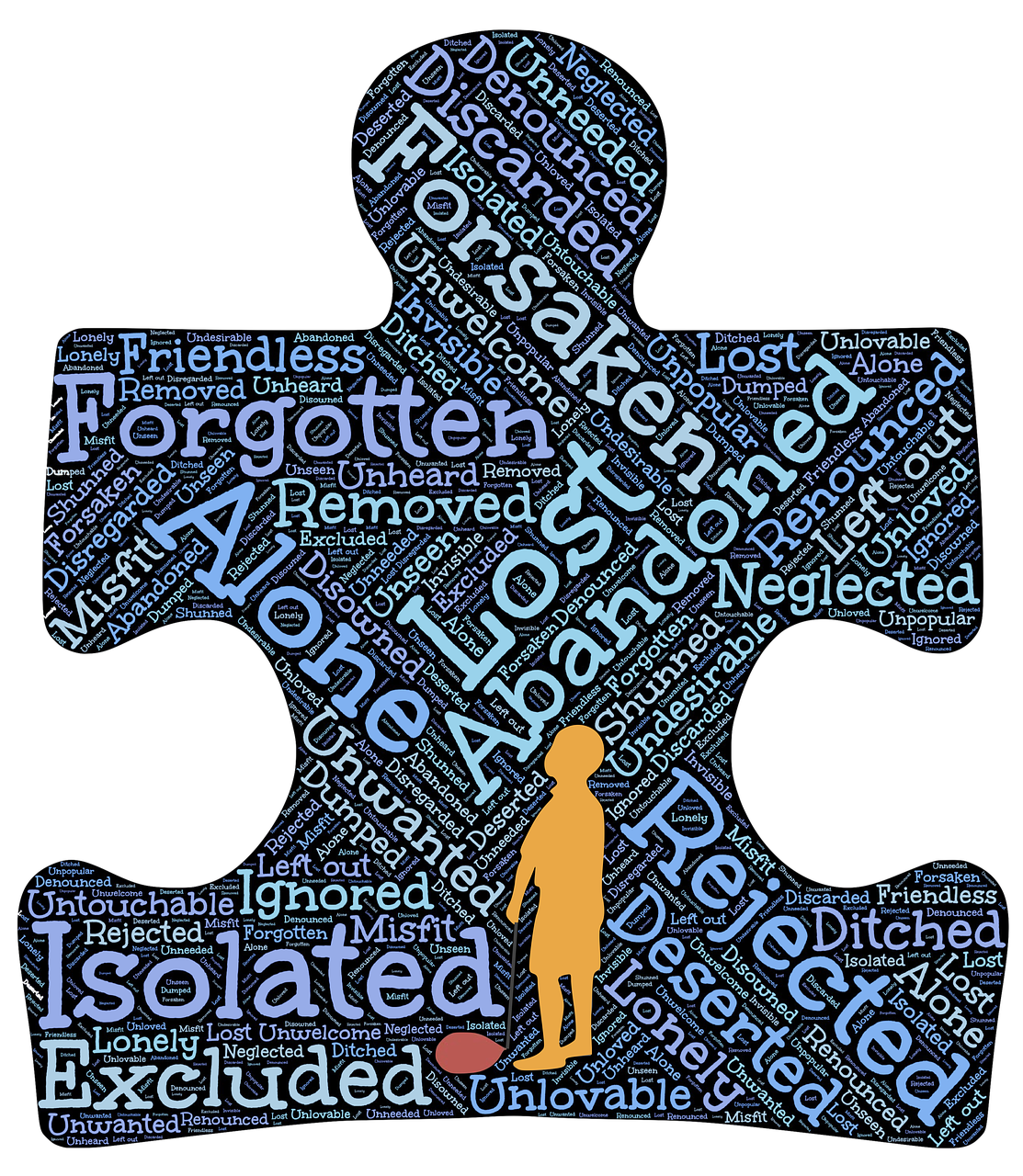

My work over the last twenty years working directly with children has shown me the range of sometimes overwhelming challenges children and young people have to face and overcome to attend school regularly. Some are terrified of bullies, some feel they can’t match up to the relentless ‘high expectations’ and academic demands of school, accentuated by the push for a ‘knowledge rich’ curriculum. Some are caught between the competing demands of school attendance and their need to stay at home to take care of a family member. Some have such fragile mental health and wellbeing they feel safe only at home in their room.

Then there are those facing challenges generated by their school, among them performance driven practices which intentionally exclude children from the safety of their school community, the top rung in the ladder of punishment focused behaviour management systems. The exclusion data tells us who these children are; most commonly they’re the persistent low-level classroom disrupters, the outspoken, the day-dreamers, the jokers, the ones with known or unknown special educational and health needs. Rarely they’re physically and verbally confrontational and very rarely physically violent. In my experience all these non-attenders share some things in common; personal, social, health and learning challenges that given the right support they can overcome. A failure of the exclusionary process is that it doesn’t routinely use data that trigger exclusions as indicators of the child’s needs, the drivers of ‘behaviour’, and fails to integrate support matching these needs.

A second thread is introduced by Tamsin Ford, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, who explains that the impact of exclusion on young people’s mental health can be significant.

“We know that having a mental health condition, particularly a neurodevelopmental disorder such as ADHD, makes it far more likely that you will be excluded. However, we also know that being excluded makes you more likely to develop a mental health condition. I tracked a group of children for three years, and found that even when you take out those that initially had a mental health condition, being excluded predicted having a mental health condition three years down the line.”

In the last century positioning of absence from school was seen as an emotional problem and truancy a matter of bad children misbehaving. In 2022 the view is “more nuanced .. in fact, our research demonstrates a stronger association between depression and unauthorised absence. Teenagers who are really struggling in school, being bullied or very socially isolated and can’t cope (or) where they can’t just go home, … will truant. …. I think exclusion is a very blunt tool, and it needs to be used cautiously, if at all. And if we’re excluding a child repeatedly who has special educational needs, it would suggest to me a system failure to support that child.”

What to do?

In a third thread, Dame Rachel de Souza, the newly appointed Children’s Commissioner, has been talking about mental health and how children should be supported;

“What they are asking for is not rocket science: they want someone to talk to when they’re worried or upset. They want easier access to support when problems are emerging so that they don’t start to build up. I believe that as adults we need to listen to what children say and respond. It is clear from the Big Ask that children’s mental health will be a top priority for me in my role as Children’s Commissioner.”

Professor Ford suggests something similar, and equally complex;

“It means a whole-school ethos that promotes connectedness and strong positive relationships, and that we need to take things like bullying very seriously. Bullying will happen in all schools at some point or other. It’s not so much whether it happens or not; it’s how it’s dealt with when it does happen that makes the difference. There are lots of evidence-based programmes or techniques that demonstrate an impact in reducing bullying and improving wellbeing. We’re just really lousy at implementing them, and we really need to up our game. To be clear, I’m not blaming teachers here; it’s more about whole-school priorities.”

None of this suggests a move towards more rigid discipline and the increased use of punishment in an attempt to stamp out differences in how children manage themselves in school, if they can get there. It does lead towards the combined approach of a simple set of rules and reminders to maintain community cohesiveness and prioritise classroom learning and child-centred support where children’s needs point to this, towards the same ends.

Listening actively to what children say and responding effectively means having a clear idea about what kind of relationship underpins what kind of conversation leading to a response that empowers and includes all children, the noisy ones and the quiet ones. Building a whole-school ethos that promotes connectedness and strong positive relationships demands answers to these same questions. Long-term, strengths-based outcome focused work.

There isn’t a simple answer. It is indeed rocket science. Complexity is the key, not backing away from it by holding on to outdated and unevidenced strategies, but engaging with it in the ways that humans relate and communicate at fundamental levels. My own research path led me to Solution Focused Brief Therapy in 2001 and my application of it since then, Solutions Focused Coaching in Schools. It has proven valuable as a simple approach to complex problems and may be coming to schools near you, funded and promoted by the charity PennyAppealUK. We’re looking for schools to partner us. We’re upping our game.

Small steps to a brighter future, reviving optimism.